Digitization is rewriting the rules of competition, with incumbent companies most at risk of being left behind. Here are six critical decisions CEOs must make to address the strategic challenge posed by the digital revolution.

The board of a large European insurer was pressing management for answers. A company known mostly for its online channel had begun to undercut premiums in a number of markets and was doing so without agents, building on its dazzling brand reputation online and using new technologies to engage buyers. Some of the insurer’s senior managers were sure the threat would abate. Others pointed to serious downtrends in policy renewals among younger customers avidly using new web-based price-comparison tools. The board decided that the company needed to quicken its digital pace.

For many leaders, this story may sound familiar, harkening back to the scary days, 15 years ago, when they encountered the first wave of Internet competitors. Many incumbents responded effectively to these threats, some of which in any event dissipated with the dot-com crash. Today’s challenge is different. Robust attackers are scaling up with incredible speed, inserting themselves artfully between you and your customers and zeroing in on lucrative value-chain segments.

The digital technologies underlying these competitive thrusts may not be new, but they are being used to new effect. Staggering amounts of information are accessible as never before—from proprietary big data to new public sources of open data. Analytical and processing capabilities have made similar leaps with algorithms scattering intelligence across digital networks, themselves often lodged in the cloud. Smart mobile devices make that information and computing power accessible to users around the world.

As these technologies gain momentum, they are profoundly changing the strategic context: altering the structure of competition, the conduct of business, and, ultimately, performance across industries. One banking CEO, for instance, says the industry is in the midst of a transition that occurs once every 100 years. To stay ahead of the unfolding trends and disruptions, leaders across industries will need to challenge their assumptions and pressure-test their strategies.

Opportunities and threats

Digitization often lowers entry barriers, causing long-established boundaries between sectors to tumble. At the same time, the “plug and play” nature of digital assets causes value chains to disaggregate, creating openings for focused, fast-moving competitors. New market entrants often scale up rapidly at lower cost than legacy players can, and returns may grow rapidly as more customers join the network.1

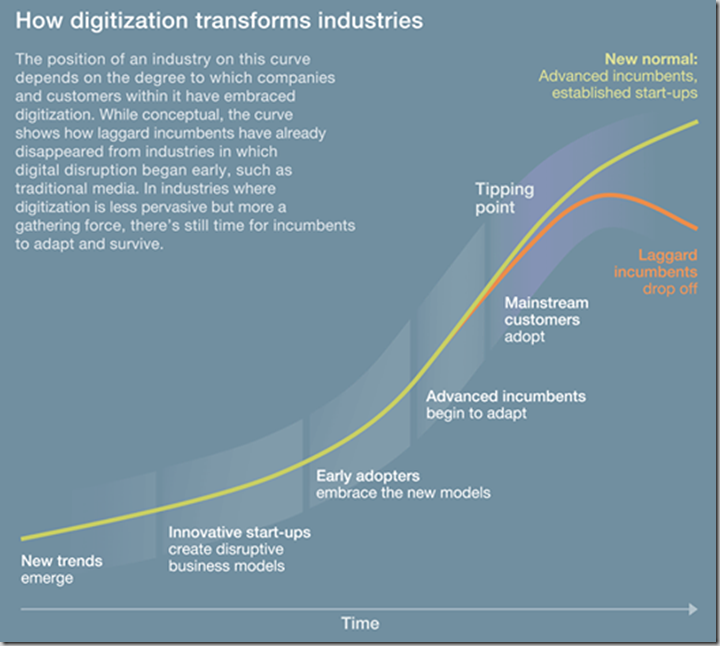

Digital capabilities increasingly will determine which companies create or lose value. Those shifts take place in the context of industry evolution, which isn’t monolithic but can follow a well-worn path: new trends emerge and disruptive entrants appear, their products and services embraced by early adopters (exhibit). Advanced incumbents then begin to adjust to these changes, accelerating the rate of customer adoption until the industry’s level of digitization—among companies but, perhaps more critically, among consumers as well—reaches a tipping point. Eventually, what was once radical is normal, and unprepared incumbents run the risk of becoming the next Blockbuster. Others, which have successfully built new capabilities (as Burberry did in retailing), become powerful digital players. (See the accompanying article, “The seven habits of highly effective digital enterprises.”) The opportunities for the leaders include:

- Enhancing interactions among customers, suppliers, stakeholders, and employees. For many transactions, consumers and businesses increasingly prefer digital channels, which make content universally accessible by mixing media (graphics and video, for example), tailoring messages for context (providing location or demographic information), and adding social connectivity (allowing communities to build around themes and needs, as well as ideas shared among friends). These channels lower the cost of transactions and record them transparently, which can help in resolving disputes.

- Improving management decisions as algorithms crunch big data from social technologies or the Internet of Things. Better decision making helps improve performance across business functions—for example, providing for finer marketing allocations (down to the level of individual consumers) or mitigating operational risks by sensing wear and tear on equipment.

- Enabling new business or operating models, such as peer-to-peer product innovation or customer service. China’s Xiaomi crowdsources features of its new mobile phones rather than investing heavily in R&D, and Telstra crowdsources customer service, so that users support each other to resolve problems without charge. New business or operating models can also disintermediate existing customer–supplier relations—for example, when board-game developers or one-person shops manufacture products using 3-D printers and sell directly to Amazon.

The upshot is that digitization will change industry landscapes as it gives life to new sets of competitors. Some players may consider your capabilities a threat even before you have identified them as competitors. Indeed, the forces at work today will bring immediate challenges, opportunities—or both—to literally all digitally connected businesses.

Seven forces at work

Our research and experience with leading companies point to seven trends that could redefine competition.

1. New pressure on prices and margins

Digital technologies create near-perfect transparency, making it easy to compare prices, service levels, and product performance: consumers can switch among digital retailers, brands, and services with just a few clicks or finger swipes. This dynamic can commoditize products and services as consumers demand comparable features and simple interactions. Some banks, for instance, now find that simplifying products for easy purchase on mobile phones inadvertently contributes to a convergence between their offerings and those of competitors that are also pursuing mobile-friendly simplicity.

Third parties have jumped into this fray, disintermediating relationships between companies and their customers. The rise of price-comparison sites that aggregate information across vendors and allow consumers to compare prices and service offerings easily is a testament to this trend. In Europe, chain retailers, which traditionally dominate fast-moving consumer goods, have seen their revenues fall as customers flock to discounters after comparing prices even for staples like milk and bread. In South Korea, online aggregator OK Cashbag has inserted itself into the consumer’s shopping behavior through a mobile app that pools product promotions and loyalty points for easy use across more than 50,000 merchants.

These dynamics create downward pressure on returns across consumer-facing industries, and the disruptive currents are now rippling out to B2B businesses.

2. Competitors emerge from unexpected places

Digital dynamics often undermine barriers to entry and long-standing sources of product differentiation. Web-based service providers in telecommunications or insurance, for example, can now tap markets without having to build distribution networks of offices and local agents. They can compete effectively by mining data on risks and on the incomes and preferences of customers.

At the same time, the expense of building brands online and the degree of consumer attention focused on a relatively small number of brands are redrawing battle lines in many markets. Singapore Post is investing in an e-commerce business that benefits from the company’s logistics and warehousing backbone. Japanese web retailer Rakuten is using its network to offer financial services. Web powerhouses like Google and Twitter eagerly test industry boundaries through products such as Google Wallet and Twitter’s retail offerings.

New competitors can often be smaller companies that will never reach scale but still do a lot of damage to incumbents. In the retailing industry, for instance, entrepreneurs are cherry-picking subcategories of products and severely undercutting pricing on small volumes, forcing bigger companies to do the same.

3. Winner-takes-all dynamics

Digital businesses reduce transaction and labor costs, increase returns to scale from aggregated data, and enjoy increases in the quality of digital talent and intellectual property as network effects kick in. The cost advantages can be significant: online retailers may generate three times the level of revenue per employee as even the top-performing discounters. Comparative advantage can materialize rapidly in these information-intensive models—not over the multiyear spans most companies expect.

Scale economies in data and talent often are decisive. In insurance, digital “natives” with large stores of consumer information may navigate risks better than traditional insurers do. Successful start-ups known for digital expertise and engineer-friendly cultures become magnets for the best digital talent, creating a virtuous cycle. These effects will accelerate consolidation in the industries where digital scale weighs most heavily, challenging more capital- and labor-intensive models. In our experience, banking, insurance, media, telecommunications, and travel are particularly vulnerable to these winner-takes-all market dynamics.

In France, for instance, the start-up Free has begun offering mobile service supported by a large and active digital community of “brand fans” and advocates. The company nurtures opinion-leader “alpha fans,” who interact with the rest of the base on the Internet via blogs, social networks, and other channels, building a wave of buzz that quickly spreads across the digital world. Spending only modestly on traditional marketing, Free nonetheless has achieved high levels of customer satisfaction through its social-media efforts—and has gained substantial market share.2

4. Plug-and-play business models

As digital forces reduce transaction costs, value chains disaggregate. Third-party products and services—digital Lego blocks, in effect—can be quickly integrated into the gaps. Amazon, for instance, offers businesses logistics, online retail “storefronts,” and IT services. For many businesses, it may not pay to build out those functions at competitive levels of performance, so they simply plug an existing offering into their value chains. In the United States, registered investment advisers have been the fastest-growing segment3 of the investment-advisory business, for example. They are expanding so fast largely because they “insource” turnkey systems (including record keeping and operating infrastructure) purchased from Charles Schwab, Fidelity, and others that give them all the capabilities they need. With a license, individuals or small groups can be up and running their own firms.

In the travel industry, new portals are assembling entire trips: flights, hotels, and car rentals. The stand-alone offerings of third parties, sometimes from small companies or even individuals, plug into such portals. These packages are put together in real time, with dynamic pricing that depends on supply and demand. As more niche providers gain access to the new platforms, competition is intensifying.

5. Growing talent mismatches

Software replaces labor in digital businesses. We estimate, for instance, that of the 700 end-to-end processes in banks (opening an account or getting a car loan, for example), about half can be fully automated. Computers increasingly are performing complex tasks as well. “Brilliant machines,” like IBM’s Watson, are poised to take on the work of many call-center workers. Even knowledge-intensive areas, such as oncology diagnostics, are susceptible to challenge by machines: thanks to the ability to scan and store massive amounts of medical research and patients’ MRI results, Watson diagnoses cancers with much higher levels of speed and accuracy than skilled physicians do. Digitization will encroach on a growing number of knowledge roles within companies as they automate many frontline and middle-management jobs based upon synthesizing information for C-level executives.

At the same time, companies are struggling to find the right talent in areas that can’t be automated. Such areas include digital skills like those of artificial-intelligence programmers or data scientists and of people who lead digital strategies and think creatively about new business designs. A key challenge for senior managers will be sensitively reallocating the savings from automation to the talent needed to forge digital businesses. One global company, for example, is simultaneously planning to cut more than 10,000 employees (some through digital economies) while adding 3,000 to its digital business. Moves like these, writ large, could have significant social repercussions, elevating the opportunities and challenges associated with digital advances to a public-policy issue, not just a strategic-business one.

6. Converging global supply and demand

Digital technologies know no borders, and the customer’s demand for a unified experience is raising pressure on global companies to standardize offerings. In the B2C domain, for example, many US consumers are accustomed to e-shopping in the United Kingdom for new fashions (see sidebar, “How digitization is reshaping global flows”). They have come to expect payment systems that work across borders, global distribution, and a uniform customer experience.

Sidebar

How digitization is reshaping global flows

In B2B markets from banking to telecommunications, corporate purchasers are raising pressure on their suppliers to offer services that are standardized across borders, integrate with other offerings, and can be plugged into the purchasing companies’ global business processes easily. One global bank has aligned its offerings with the borderless strategies of its major customers by creating a single website, across 20 countries, that integrates what had been an array of separate national or product touch points. A US technology company has given each of its larger customers a customized global portal that allows it to get better insights into their requirements, while giving them an integrated view of global prices and the availability of components.

7. Relentlessly evolving business models—at higher velocity

Digitization isn’t a one-stop journey. A case in point is music, where the model has shifted from selling tapes and CDs (and then MP3s) to subscription models, like Spotify’s. In transportation, digitization (a combination of mobile apps, sensors in cars, and data in the cloud) has propagated a powerful nonownership model best exemplified by Zipcar, whose service members pay to use vehicles by the hour or day. Google’s ongoing tests of autonomous vehicles indicate even more radical possibilities to shift value. As the digital model expands, auto manufacturers will need to adapt to the swelling demand of car buyers for more automated, safer features. Related businesses, such as trucking and insurance, will be affected, too, as automation lowers the cost of transportation (driverless convoys) and “crash-less” cars rewrite the existing risk profiles of drivers.

Managing the strategic challenges: Six big decisions

Rethinking strategy in the face of these forces involves difficult decisions and trade-offs. Here are six of the thorniest.

Decision 1: Buy or sell businesses in your portfolio?

The growth and profitability of some businesses become less attractive in a digital world, and the capabilities needed to compete change as well. Consequently, the portfolio of businesses within a company may have to be altered if it is to achieve its desired financial profile or to assemble needed talent and systems.

Tesco has made a number of significant digital acquisitions over a two-year span to take on digital competition in consumer electronics. Beauty-product and fragrance retailer Sephora recently acquired Scentsa, a specialist in digital technologies that improve the in-store shopping experience. (Scentsa touch screens access product videos, link to databases on skin care and fragrance types, and make product recommendations.) Sephora officials said they bought the company to keep its technology out of competitors’ reach and to help develop in-store products more rapidly.4

Companies that lack sufficient scale or expect a significant digital downside should consider divesting businesses. Some insurers, for instance, may find themselves outmatched by digital players that can fine-tune risks. In media, DMGT doubled down on an investment in their digital consumer businesses, while making tough structural decisions on their legacy print assets, including the divestment of local publications and increases in their national cover price. Home Depot continues to shift its investment strategy away from new stores to massive new warehouses that serve growing online sales. This year it bought Blinds.com, adding to a string of website acquisitions.5

Decision 2: Lead your customers or follow them?

Incumbents too have opportunities for launching disruptive strategies. One European real-estate brokerage group, with a large, exclusively controlled share of the listings market, decided to act before digital rivals moved into its space. It set up a web-based platform open to all brokers (many of them competitors) and has now become the leading national marketplace, with a growing share. In other situations, the right decision may be to forego digital moves—particularly in industries with high barriers to entry, regulatory complexities, and patents that protect profit streams.

Between these extremes lies the all-too-common reality that digital efforts risk cannibalizing products and services and could erode margins. Yet inaction is equally risky. In-house data on existing buyers can help incumbents with large customer bases develop insights (for example, in pricing and channel management) that are keener than those of small attackers. Brand advantages too can help traditional players outflank digital newbies.

Decision 3: Cooperate or compete with new attackers?

A large incumbent in an industry that’s undergoing digital disruption can feel like a whale attacked by piranhas. While in the past, there may have been one or two new entrants entering your space, there may be dozens now—each causing pain, with none individually fatal. PayPal, for example, is taking slices of payment businesses, and Amazon is eating into small-business lending. Companies can neutralize attacks by rapidly building copycat propositions or even acquiring attackers. However, it’s not feasible to defend all fronts simultaneously, so cooperation with some attackers can make more sense than competing.

Santander, for instance, recently went into partnership with start-up Funding Circle. The bank recognized that a segment of its customer base wanted access to peer-to-peer lending and in effect acknowledged that it would be costly to build a world-class offering from scratch. A group of UK banks formed a consortium to build a mobile-payment utility (Paym) to defend against technology companies entering their markets. British high-end grocer Waitrose collaborated with start-up Ocado to establish a digital channel and home distribution before eventually creating its own digital offering.

Digital technologies themselves are opening pathways to collaborative forms of innovation. Capital One launched Capital One Labs, opening its software interfaces to multiple third parties, which can defend a range of spaces along their value chains by accessing Capital One’s risk- and credit-assessment capabilities without expending their own capital.

Decision 4: Diversify or double down on digital initiatives?

As digital opportunities and challenges proliferate, deciding where to place new bets is a growing headache for leaders. Diversification reduces risks, so many companies are tempted to let a thousand flowers bloom. But often these small initiatives, however innovative, don’t get enough funding to endure or are easily replicated by competitors. One answer is to think like a private-equity fund, seeding multiple initiatives but being disciplined enough to kill off those that don’t quickly gain momentum and to bankroll those with genuinely disruptive potential. Since 2010, Merck’s Global Health Innovation Fund, with $500 million under management, has invested in more than 20 start-ups with positions in health informatics, personalized medicine, and other areas—and it continues to search for new prospects. Other companies, such as BMW and Deutsche Telekom, have set up units to finance digital start-ups.

The alternative is to double down in one area, which may be the right strategy in industries with massive value at stake. A European bank refocused its digital investments on 12 customer decision journeys,6 such as buying a house, that account for less than 5 percent of its processes but nearly half of its cost base. A leading global pharmaceutical company has made significant investments in digital initiatives, pooling data with health insurers to improve rates of adherence to drug regimes. It is also using data to identify the right patients for clinical trials and thus to develop drugs more quickly, while investing in programs that encourage patients to use monitors and wearable devices to track treatment outcomes. Nordstrom has invested heavily to give its customers multichannel experiences. It focused initially on developing first-class shipping and inventory-management facilities and then extended its investments to mobile-shopping apps, kiosks, and capabilities for managing customer relationships across channels.

Decision 5: Keep digital businesses separate or integrate them with current nondigital ones?

Integrating digital operations directly into physical businesses can create additional value—for example, by providing multichannel capabilities for customers or by helping companies share infrastructure, such as supply-chain networks. However, it can be hard to attract and retain digital talent in a traditional culture, and turf wars between the leaders of the digital and the main business are commonplace. Moreover, different businesses may have clashing views on, say, how to design and implement a multichannel strategy.

One global bank addressed such tensions by creating a groupwide center of excellence populated by digital specialists who advise business units and help them build tools. The digital teams will be integrated with the units eventually, but not until the teams reach critical mass and notch a number of successes. The UK department-store chain John Lewis bought additional digital capabilities with its acquisition of the UK division of Buy.com,7 in 2001, ultimately combining it with the core business. Wal-Mart Stores established its digital business away from corporate headquarters to allow a new culture and new skills to grow. Hybrid approaches involving both stand-alone and well-integrated digital organizations are possible, of course, for companies with diverse business portfolios.

Decision 6: Delegate or own the digital agenda?

Advancing the digital agenda takes lots of senior-management time and attention. Customer behavior and competitive situations are evolving quickly, and an effective digital strategy calls for extensive cross-functional orchestration that may require CEO involvement. One global company, for example, attempted to digitize its processes to compete with a new entrant. The R&D function responsible for product design had little knowledge of how to create offerings that could be distributed effectively over digital channels. Meanwhile, a business unit under pricing pressure was leaning heavily on functional specialists for an outsize investment to redesign the back office. Eventually, the CEO stepped in and ordered a new approach, which organized the digitization effort around the decision journeys of clients.

Faced with the need to sort through functional and regional issues related to digitization, some companies are creating a new role: chief digital officer (or the equivalent), a common way to introduce outside talent with a digital mind-set to provide a focus for the digital agenda. Walgreens, a well-performing US pharmacy and retail chain, hired its president of digital and chief marketing officer (who reports directly to the CEO) from a top technology company six years ago. Her efforts have included leading the acquisition of drugstore.com, which still operates as a pure play. The acquisition upped Walgreens’ skill set, and drugstore.com increasingly shares its digital infrastructure with the company’s existing site: walgreens.com.

Relying on chief digital officers to drive the digital agenda carries some risk of balkanization. Some of them, lacking a CEO’s strategic breadth and depth, may sacrifice the big picture for a narrower focus—say, on marketing or social media. Others may serve as divisional heads, taking full P&L responsibility for businesses that have embarked on robust digital strategies but lacking the influence or authority to get support for execution from the functional units.

Alternatively, CEOs can choose to “own” and direct the digital agenda personally, top down. That may be necessary if digitization is a top-three agenda item for a company or group, if digital businesses need substantial resources from the organization as a whole, or if pursuing new digital priorities requires navigating political minefields in business units or functions.

Regardless of the organizational or leadership model a CEO and board choose, it’s important to keep in mind that digitization is a moving target. The emergent nature of digital forces means that harnessing them is a journey, not a destination—a relentless leadership experience and a rare opportunity to reposition companies for a new era of competition and growth.

About the authors

Martin Hirt is a director in McKinsey’s Taipei office, and Paul Willmott is a director in the London office.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of ’Tunde Olanrewaju and Meng Wei Tan to this article.

No comments:

Post a Comment